The History of the Calculator

Author: calchub.tech team

Reviewed for accuracy and clarity by the calchub.tech research team

Calculators feel normal today, but their story shows how fast technology can change. What started as a simple way to count has become a powerful tool that solves complex problems instantly. As a team that builds, tests, and studies calculators every day, we’ve seen how these tools evolved from physical objects into digital systems that quietly support work, education, and daily life.

Understanding the history of the calculator helps explain why modern calculators work the way they do and why dedicated calculator tools still matter, even in the age of smartphones.

Calculation Beginnings: The Mechanical Age

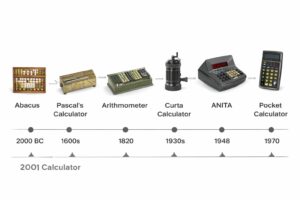

Long before calculators reached their modern form in the 1990s, people relied on physical tools to perform calculations. This journey stretches across nearly four thousand years and shows how slowly early calculation methods evolved.

All-in-one calculator hub covering personal finance, health and science, everyday life tools, and education and planning to help you calculate, understand, and plan with confidence.

The Abacus and Early Counting Tools

The earliest known calculator was the abacus. It was a hand-operated mechanical calculator made from beads and rods, first used by Sumerians and Egyptians around 2000 BC. A simple frame held sliding beads, with each row representing tens, hundreds, and higher values.

This design made addition and subtraction faster and less error-prone. It was especially useful for traders and early accountants, sometimes called bean counters. Despite its simplicity, the abacus remained effective for centuries.

From Stillness to Mathematical Progress

For almost 3,600 years, calculation technology changed very little. That began to shift in 17th-century Europe, when advances in mathematics opened new possibilities. The discovery of logarithms by John Napier allowed tools like the slide rule to be developed by Edward Gunter and William Oughtred.

The slide rule used logarithmic scales to support multiplication, division, trigonometry, exponentials, and square roots. Even into the 1980s, slide rules were part of mathematics education for many schoolchildren.

Portability played a key role. Unlike heavy mechanical or electric machines, a slide rule could fit into a shirt pocket. Famous examples include rocket scientists using slide rules during space missions, including Apollo 13 in 1970.

Gears, Wheels, and Buttons

The next major shift came with machines that automated arithmetic more fully.

Early Mechanical Calculators

In 1642, French intellectual Blaise Pascal created a mechanical calculator designed to perform arithmetic operations without relying on human intelligence. Using geared wheels, Pascal’s machine could add and subtract directly and multiply or divide through repetition.

Later, Gottfried Leibniz introduced the Leibniz wheel, aiming to create a true four-operation calculator. Although his designs were influential, a fully practical machine arrived later.

Commercial Mechanical Machines

In 1820, Thomas de Colmar patented the Arithmometer in France. This became the first commercially viable counting machine and was produced from 1851 to 1915. It spread across Europe and helped standardize office calculations.

Innovation soon moved to the United States. Machines like the Grant Mechanical Calculating Machine (1877) and the P100 Burroughs Adding Machine (1886) became common in offices. These machines built entire industries and shaped modern accounting practices.

In 1887, Dorr E. Felt introduced the Comptometer, a key-driven calculator that marked the beginning of the push-button age. Mechanical calculators reached their peak with the Curta calculator in 1948, a compact, pocket-sized device that dominated office life until electronics took over in the late 1960s.

Business Calculators: The Electronic Age

The electronic calculator emerged from military and scientific needs during the late 1930s.

War, Computing, and Electronics

World War II created demand for rapid calculations in trigonometry, targeting, and navigation. Systems like the Sperry-Norden bombsight, the Torpedo Data Computer, and the Kerrison Predictor combined mechanical components with electrical outputs.

During the war, code-breaking efforts produced Colossus, the first all-electronic computer. It used Boolean logic and thermionic valves but was highly specialized.

ENIAC and Early Electronic Computing

In 1946, ENIAC (Electronic Numerical Integrator and Computer) was built as an artillery firing table calculator. It could solve a wide range of numerical problems and perform basic arithmetic functions.

ENIAC was incredibly powerful for its time but impractical. It used thousands of vacuum tubes, occupied massive floor space, consumed enormous power, and weighed tens of tonnes. Still, it proved that fully electronic calculation was possible.

Valve and Tube Calculators

Electronic calculators for offices became practical only after components were miniaturized.

The First Desktop Electronic Calculators

In 1961, ANITA (A New Inspiration To Arithmetic / Accounting) became the world’s first all-electronic desktop calculator. Developed in Britain by Control Systems Ltd and sold under Bell Punch and Sumlock, ANITA used push-button input with electronic switching inside.

It relied on semiconductor diodes, gas-filled valves, and Nixie tubes for its illuminated display. Although expensive, tens of thousands were sold before transistor-based competitors entered the market in the mid-1960s.

The Transistor Age

Transistors replaced bulky valves and opened the door to smaller, faster, and more reliable calculators.

Manufacturers such as Canon, Olivetti, Toshiba, Sony, Wang, and others released new designs. Machines like the Olivetti Programma 101, introduced in 1965, used magnetic cards and a built-in printer and are often considered early personal computers.

Despite improvements, these machines were still large and expensive. A major turning point arrived in 1967, when Texas Instruments introduced the Cal Tech prototype, a handheld calculator capable of basic operations.

Pocket Calculators and the Microchip Age

The shift from desktop machines to pocket calculators was driven by integrated microchips, lower power consumption, and compact designs.

Microchips Change Everything

By the late 1960s, partnerships between calculator manufacturers and semiconductor companies accelerated innovation. Calculators like the Sharp QT-8D and QT-8B became portable and battery powered.

In 1970, the Busicom LE-120 Handy became the first true pocket calculator. It used LED displays and ran on AA batteries, marking the start of personal electronic calculation.

Calculators in the Virtual Age

By 1980, calculators had reached a familiar form: compact bodies, LCD displays, silicone keyboards, and solar or button-battery power. Prices dropped sharply, and calculators became widely available.

Graphing calculators arrived in the mid-1980s, led by models like the Casio fx-7000G. These tools supported algebra, graphing, and programming and became standard in classrooms and exams.

Manufacturers also began targeting specific users, such as students, engineers, and financial professionals.

Mobile Devices and Software Calculators

The rise of smartphones and tablets changed how people access calculators.

Early devices like the IBM Simon combined phone functions with basic computing tools. Later smartphones and tablets turned calculators into software applications, including advanced graphing and scientific tools.

Despite this shift, physical calculators remain widely sold, with hundreds of models still available worldwide.

The Future of Calculators

Calculators continue to exist because they are optimized for specific tasks. Many users prefer physical devices for speed, accuracy, and reliability, especially in exams and professional environments.

Desk calculators remain common in offices due to ergonomic advantages and printing functions. Simple, non-connected calculators are also trusted in academic settings where smartphones are restricted.

While technology continues to evolve, calculators still play a meaningful role in how people work with numbers today.

Sources and Research Notes

Historical references align with records from institutions such as the Computer History Museum, NASA mission archives, and academic histories of computing and mathematics.